Incentives drive behavior

Leverage incentives to improve your work relationships and your emotional relationship with work

A key tenet of human nature is that incentives drive behavior. Consider, for example, how people are motivated to exercise three times a week with the reward of indulging in a dessert. Similarly, disincentives work in the opposite way. An expensive speeding ticket prevents drivers from going past the speed limit.

As I’ve progressed in my career, I have found that incentives are found at every level of company. They shape the relationship that individuals have with their job. Teams and coworkers work well together when their incentives are aligned. Even more so, understanding what leaders want comes down to their individual and team motives. I have realized that uncovering internal and external motivations is key to excelling and thriving at your job, especially in larger corporations.

This article dives into:

A framework for thinking about incentives

How to leverage incentive theory to improve your work relationships

How to self-reflect to have a better emotional relationship with work

A framework for thinking about incentives

As early as 1938, Winston Churchill wrote a letter evoking the “carrot and the stick” metaphor. The carrot refers to rewards given to individuals to drive intended behavior, while the stick refers to punishments to prevent unintended behavior. The carrot and the stick are also commonly referred to as incentives and disincentives.1

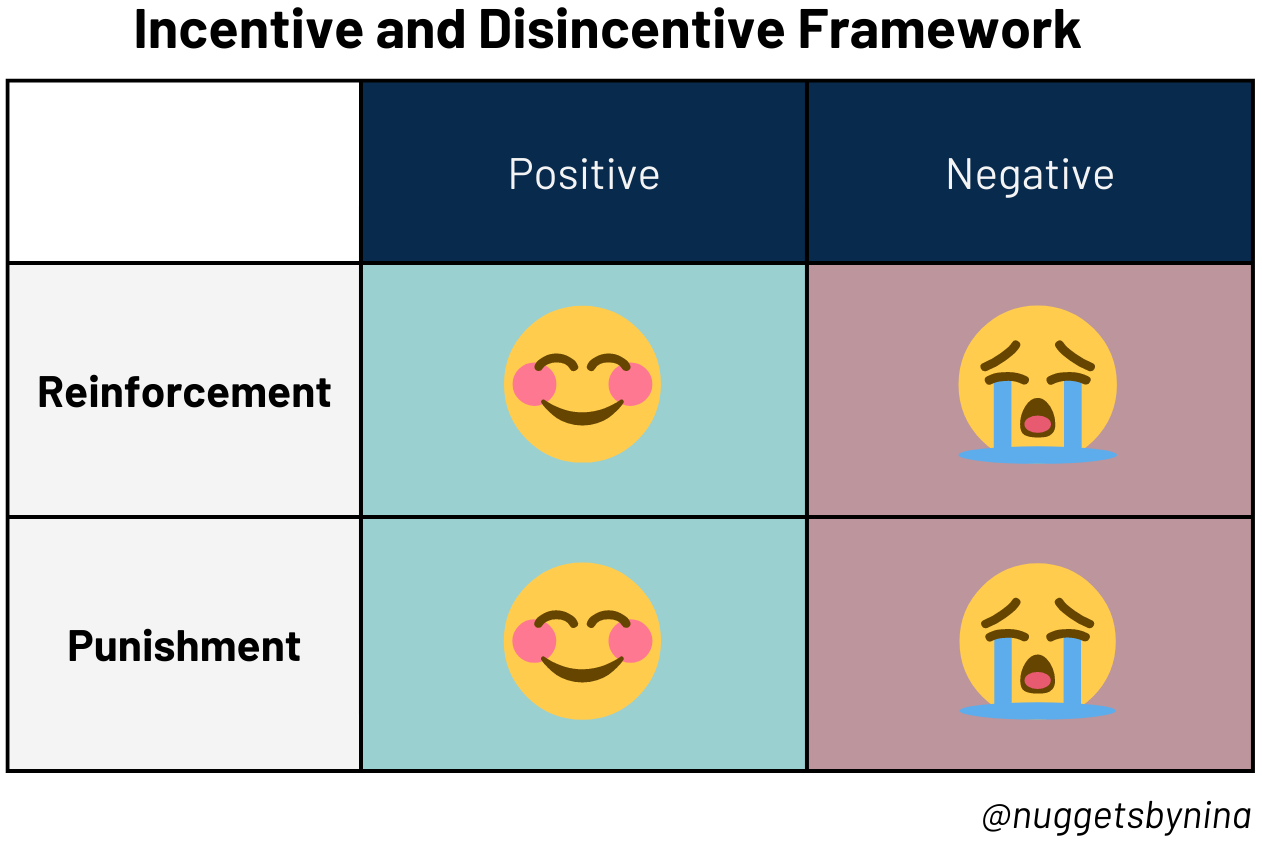

A 2-by-2 matrix is a powerful vehicle to understand the different incentive and disincentive scenarios. In the visualization below, the two rows represent reinforcement (encouragement or strengthening) and punishment (infliction or imposition). The two columns represent an whether the reinforcement or punishment is positive or negative. Each box represents an individual’s emotions as a result of reinforcements and punishments. What drives happiness is referred to as incentives (happy emoji), while what drives sadness is referred to as disincentives (sad emoji).

Walking through the main four boxes helps us understand different (dis)incentive vehicles:

Top-left = Positive Reinforcement: Rewarding one for good behavior, resulting in increased desirable behavior. Example: Giving a bonus for hitting sales targets, causing you to hit more sales targets in the future.

Top-right = Negative Reinforcement: Removing undesirable outcomes, resulting in increased desirable behavior. Example: Canceling early morning practice if a sports team wins their match, causing more wins in the future.

Bottom-left = Positive Punishment: Punishing one for bad behavior, resulting in decreased undesirable behavior. Example: Levying a fine for late book returns to a library, causing you to return books late less in the future.

Bottom-right = Negative Punishment: Depriving one of their wants or needs, resulting in decreased undesirable behavior. Example: Cutting the salary of employees making mistakes, causing them to make less mistakes in the future.

Humans are motivated to do what might bring them joy and avoid what might cause them pain.

Incentives to improve your work relationships

Applying this concept to work can improve your relationship with your peers, direct reports, manager, and leaders. I have found that as I become more and more senior, I am increasingly focused less on the business problem at hand and more on who owns the relevant decisions rights and what their associated incentives are. If misalignment exists between incentives and broader organizational goals, individuals may act in discordance with the broader organizational vision. If there is strong alignment, the decision-making process is clearer for all parties involved.

Peer-to-peer relationships

When working in a team setting and with peers, it is important to consider what their motivations and incentives are. For example, if you’re trying to convince a teammate on your team or another team to participate in or support your idea, it is much easier to convince them if you speak in their language and connect your project to their incentives. You may even consider highlighting how not working with you will result in a worse outcome for their team, product, or mandate.

Direct report relationship

When managing and inspiring others as a leader, it is imperative to understand what your direct reports are interested in and what fulfills them at work. If they are highly motivated by monetary incentives and promotion, highlight a clear action plan on how you will support them in growing their career and the pathway to the next-level promotion. If they are highly incentivized by recognition, shout them out in team meetings and recognize their work in all hands to share how their work has impacted the broader team’s mission.

Manager relationship

The relationship you have with your manager can make or break your day-to-day happiness at work. After all, employees don’t leave companies, they leave bad managers. As you think of how to foster a better relationship with your manager, consider what their motivations and incentives are. How are they evaluated at the end of a performance cycle? What are the key priorities they are investing energy into? How might you work in accordance to the team’s mission to show up better as one cohesive team?

Senior leader relationship

To influence senior leadership, start with deeply understanding what they are incentivized by (what they move towards) and what they feel threatened by (what they move away from). Tangibly, this can boil down to maximizing a top-line key performance indicator (KPI) or metric on which a leader is evaluated. Philosophically, this can involve understanding where they envision going next, both on a personal and professional level.

Incentives to improve your emotional relationship with work

A huge underlying component of understanding incentives comes down to an individual’s motivations. While it is valuable to understand what motivates others around you, it is arguably more important to consider what motivates you. If you act in accordance to your values (motivations), you will find alignment between your work and what you care about. This is super important to foster intrinsic excitement and drive, enabling you to tackle your goals head-on and wake up every morning excited about work. Cleverly, you can think about (dis)incentives to drive you towards what motivates you and away from what demotivates you.

Self motivations are hard to uncover. Some things to consider what evaluating your internal motivations for a career include:

What would you do for free? Mark Twain is quoted for the famous expression, “Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life.” While it would be nice to get paid for what you love doing, these passions or side projects may not always turn into a job. You can better understand what excites you with what you do without monetary rewards.

What ideas are always on your mind? Things you enjoy doing will inevitably be top-of-mind when you wake up and go to bed. If you’re already working, observe how you feel when you wake up for work. Do you dread each day or are you excited to tackle the challenges ahead of you? What drains you of your energy and what excites you?

What do you love to learn? Anchoring your work on topics or subjects that interest you will foster motivation to continually learn and grow. Expanding your mind can be a rewarding experience in and of itself.

What would you do if you weren’t afraid? The Meta (Facebook) offices are adorned with posters that read, “What would you do if you weren’t afraid?” This quote reminds me step out of my comfort zone even if I fear the consequences. Fear can manifest in many ways, for example, fear in not living up to societal expectations, receiving judgement from others, or disappointing yourself or your family.

—

To build better relationships with yourself and others, think about your own motivations and those of others, alongside what incentives or disincentives are in play. This can help you foster better relationships with coworkers, allowing you to influence sideways, upwards, and downwards. More importantly, critically evaluating your own motivations and applying appropriate (dis)incentives will help align your job with your values, bringing fulfillment instead of boredom or fear.

B. F. Skinner (1904-1990), an American psychologist and Harvard professor, popularized these concepts in his theory of operant conditioning. Operant behaviors, or actions under our control, are human responses to our environment and result in consequences. In child psychology, for example, a child’s behavior is impacted through positive and negative reinforcements. Much of our personalities are shaped by receiving an environmental stimulus, responding to that stimulus through behavior, and reinforcing that behavior via learned experience.